Paracervical local anaesthesia for cervical dilatation and uterine interventions

PARACERVICAL BLOCK anesthesia is a simple, safe and effective means

of relieving pain eliminates the need for depressing amounts of analgesic drugs. It involves injection of local anaesthetic around the cervix to numb nearby nerves. Cervical dilatation and uterine interventions such as: -hysteroscopy,endometrial biopsies, fractional curettage, and suction terminations, they can be performed without any analgesia or anaesthesia; with regional anaesthetic injections as with paracervical block; using oral or intravenous analgesics and sedatives; or under general anaesthesia. Many gynaecologists use paracervical block for uterine intervention

No serious maternal or fetal complications have been reported.

The principal use of paracervical block anesthesia is in relieving the pain of the first stage

of labor ,dilatation and curettage and in patients with an incomplete abortion where the relief it affords is quicker and

greater than that produced by drugs which act

on the central nervous system.

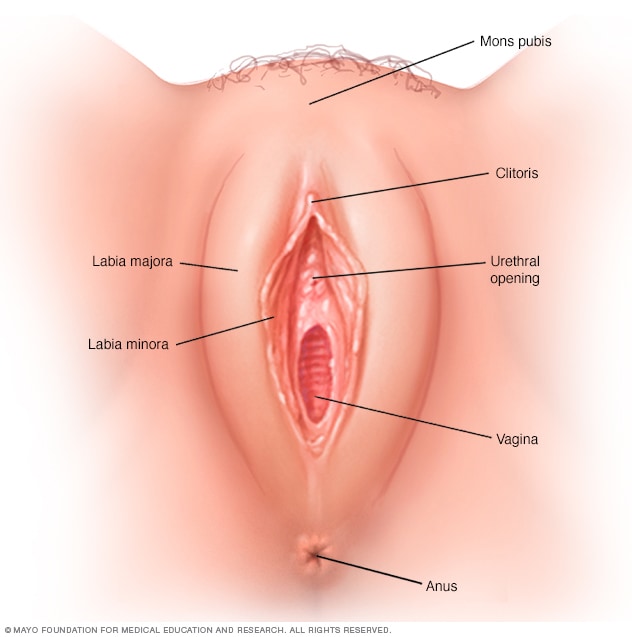

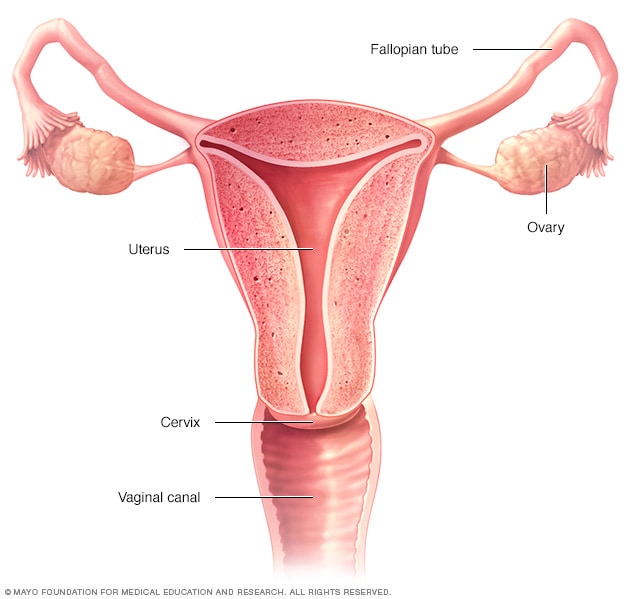

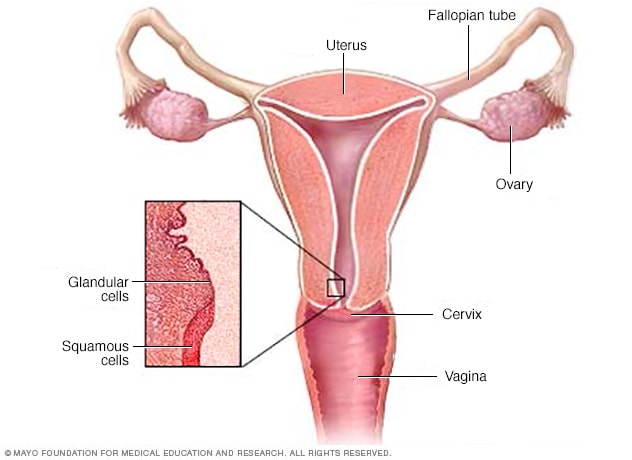

Neuroanatomy

First stage labor pain is due mainly to dilatation

of the cervix and to a lesser degree to uterine

contractions.3 The sensation of pain is due to

impulses passing by sensory and sympathetic nerve

pathways down the lateral and posterior portions

of the cervix into the area of the uterosacral ligaments. The impulses travel through the uterine,

pelvic and hypogastric plexuses into the lumbar

and lower thoracic chain to the rami of the eleventh and twelfth thoracic nerves to reach the spinal

cord. This route has been substantiated clinically

by the complete relief of pain afforded when spinal,

caudal, epidural, upper lumbar sympathetic, lower

thoracic, paravertebral, uterosacral or paracervical

block is used.

Pain of the second stage is produced primarily

by distension of the lower birth canal, vulva and

perineum and is conveyed by sensory pathways

of the pudendal nerves, which enter the spinal

cord via the posterior roots of the second, third

and fourth sacral nerves. Paracervical block, therefore, is not sufficient for delivery.

Procedure

Most anesthesiologists feel that any anesthesia,

even a local anesthesia, works more smoothly if

premedication is used. This is true with the paracervical block. I use meperidine hydrochloride

(Demerol®), promethazine hydrochloride (Phenergan®) and occasionally secobarbital sodium

(Seconal®). They are unnecessary after the block.

The Brittain Transvaginal Needle Guide* facilitates injection. This is a stainless steel tube with

a ball on one end to prevent injury to maternal tissues and a funnel on the other end to allow easy

access for the 6-inch 20-gauge needle. The needle

protrudes from the guide only 7 mm. This eliminates the danger of too deep an injection and

reduces the danger of hematoma formation to nil.

The block is performed with the patient in bed

under sterile drapes but without surgical preparation. The cervicovaginal fornix is located with

the examining finger and the guide is placed at

the 5 o'clock and 7 o'clock positions (Figure 1).

It is important to sweep the guide away from the

cervix in order to get into the posterior lateral

fornix. The needle is then inserted through the

guide, aspiration is made and the solution injected.

I use chiefly a 1 per cent solution of lidocaine

hydrochloride with epinephrine 1:1,000,000. This

is prepared by mixing 50 ml plain 1 per cent lidocaine with 5 ml 1 per cent lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000. Epinephrine is contraindicated in the presence of diseases such as diabetes,

hyperthyroidism, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, nephritis and cardiac disease. The

addition of epinephrine makes the mixture much

safer than plain lidocaine hydrochloride and allows a longer duration of effect, but at the expense

of uterine inertia in a certain proportion of cases,

sometimes requiring use of an oxytocic agent. The

usual dosage of anesthetic agent is 8 to 10 ml on

each side. The maximum dosage is 50 ml-that

is, 500 mg of lidocaine hydrochloride with epinephrine. Only 300 mg is allowed without epinephrine.

If complete anesthesia is not obtained within

two or three contractions, 5 ml is repeated on

either or both sides. Sometimes there remains an

unanesthetized coin area in the lower abdomen

on one or both sides. This can be anesthetized

by injection of 5 ml at the 10 o'clock or the 2

o'clock position. I keep one guide curved to allow

easier introduction to these anterior locations.

Failure is unacceptable. Repeated efforts should

be made until the desired effect is achieved, but

with care to stay within the limits of safe dosage.

It must be emphasized that the greatest danger is

overdosage.

The block is given in the accelerated phase of

labor, usually at about 5 cm cervical dilatation.

Using lidocaine hydrochloride with epinephrine,

the duration of anesthesia is approximately one

hour and twenty minutes.

The quality of uterine contractions after the

block might seem poor and yet the progress in cervical dilatation be dramatic. This is because

the cervix has become so soft and free of tone

that even the mild contractions lead rapidly to

complete dilatation. Because of atonicity, cervical

lacerations are rare.

We have done over four thousand blocks using

this material in private practice. There have been

no serious maternal complications. An occasional

patient has complained of feeling faint or apprehensive from too rapid absorption, but these complaints have been very transient. Temporary numbness of one or both legs noted by some patients,

disappears as the paracervical anesthesia abates.

There have been no instances of hematoma,

thrombosis, infection, hypersensitivity reaction

or lumbosacral plexus neuritis. The only untoward effect is fetal bradycardia, noted in 4.7

per cent of cases. This should not be viewed with

alarm; it is probably due to a vasovagal reflex,

and must be distinguished from fetal distress.

Infants have been delivered during the period of

bradycardia in some cases and after its disappearance in others, and in none of them has fetal depression been present. On the contrary, the

infants are breathing and crying before the delivery is completed. The important point, therefore,

is that a careful evaluation must be made to distinguish the cases of fetal bradycardia due to fetal

distress from the transient bradycardia observed

following paracervical anesthesia.

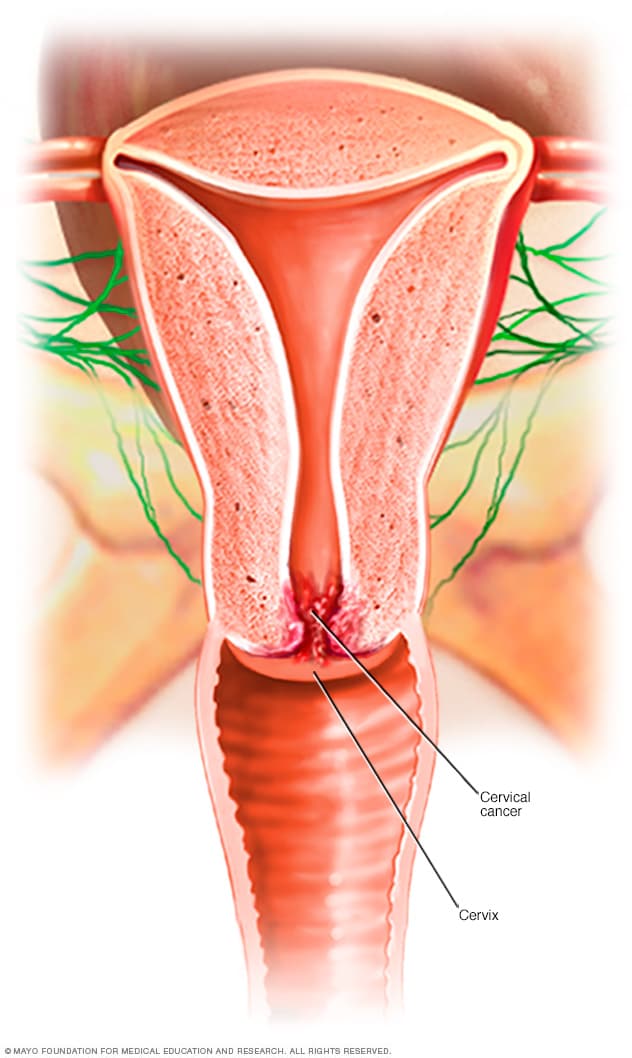

Gynecologic Use

Paracervical block for anesthesia for curettage is carried out without the Brittain Guide. A

3- or 4-inch 21-gauge needle is adequate, and

5 ml of the anesthetic solution is infiltrated at

the 4 o'clock position, 5 ml at 8 o'clock and

5 ml directly into each uterosacral ligament.

This provides the ideal anesthetic for completion of abortions and it is excellent for curettage

in many other circumstances. The method is not

recommended in the presence of vaginismus of

any cause. It is indicated where general anesthesia

or sophisticated forms of conduction anesthesia

are either unavailable or contraindicated. It is

especially useful if the patient has anemia, has too

recently eaten or has a respiratory problem or

is in borderline shock. Many patients with incomplete abortions fall into this category.

Paracervical block can also be used in other

minor procedures such as cervical repair, conization and Shirodkar or Wurm operations, although in such cases it is probably better to reserve it for the exceptionally poor risk patients.

Paracervical block has also been recommended

as an aid in the differential diagnosis of dysmenorrhea.

Book appointment today at Gyncentre : Email gyncentre@gmail.com Call / WhatsApp @ +254706666542